The Colchester Oyster Feast is world renowned. This web page aims to tell you a little about it, its beginnings,

its history and an up-to-date view of how Colchester celebrates its oysters.

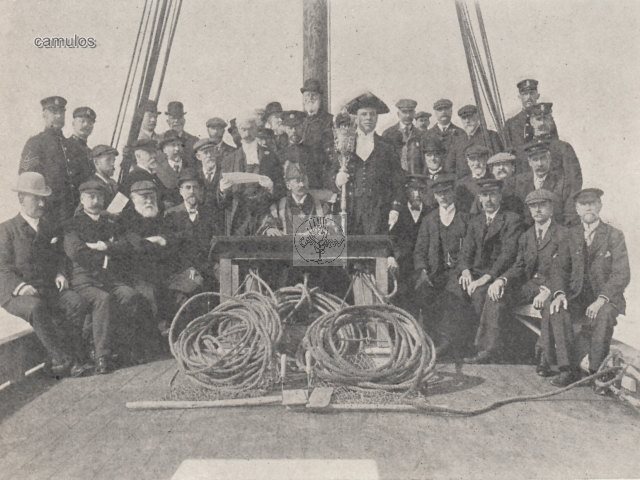

A First for the County Standard In 2005 we marked the 100th anniversary of the first press photograph. From August 1905 the Essex County Standard began to print photographs each week. One of the first was of the opening of the fishery. It was very instructive as those involved wore no ceremonial robes, the mayor cannot be seen and the town clerk, whilst present stood bare-headed at the back. The white bearded man in a top hat centre stage was none other than Henry Laver. The two dredges being hauled out were full of oysters and informed eyes were studying their quality. The gin and gingerbread came later, when, apparently for the first time, mayor, town clerk and town sergeant appeared in robes. With the publishing of this picture, we had reached the final version of the 'Opening of the Oyster Fishery', for which we credit the press, as mayor, town clerk and town sergeant pose for their photo, while the mayor 'tastes' the first oyster.

The First Catch of the Season in 1922

Gin and Gingerbread

The business event of 1905 has turned into the 'jolly' of the 21st century. For, sadly, Henry Laver's revolution did not last. Raw sewage began to contaminate Britain's oyster beds. Slipper limpets imported with American oysters decimated stocks. After the First World War 1,000 tons of TNT were dumped off the Essex coast. Sales in 1930 were one seventh of those before the war. Worse followed after the Second World War. The 1953 flood covered the 'layings' with mud and in the 1960s cold winters and a parasite called bonamia ostreae destroyed the stock. The Colne Fishery Company was finished. Only today is cautious progress being made towards improved oyster cultivation.

So, if you are still reading this, the 'Opening of the Oyster Fishery' is (like the Oyster Feast) largely what the Victorians made it. It does however carry echoes that are centuries older.

An 'ancient' tradition born in the 1960s

In 2010, Councillor Sonia Lewis, Mayor of Colchester, declared that she was not keen on going aboard a boat for the traditional opening ceremony, and so it was decided to have a land based ceremony instead, for this year only. So far as is known, no Mayor of Colchester has ever drowned, although John Clay (1827-8) broke his leg when run over by Mrs Bare's fish wagon. Mayors in those days were less risk averse.

Fortunately, John recovered to attend the Admiralty Court at the Blockhouse, East Mersea, on September 5, 1828. After a good breakfast, courtesy of the Rose and Crown, in Wivenhoe, the mayor, corporation and hangers-on went by boat - complete with band - to Mersea Stone (today the easternmost tip of Cudmore Grove). Here, they disembarked for the Blockhouse ceremony and feast, before sailing the boundary of the Oyster Fishery, returning for some merry dancing on the beach.

What we have just described is now called the Opening of the Oyster Fishery. Notice, there is no reference to dredging or tasting of oysters.

The Admiralty Court existed to try anyone guilty of fishing without a licence or fishing during the close season, which ran from April to September. It had been established in 1566 because the abundant wild oysters of the Colne had been fished out by uncontrolled dredging, partly to meet the insatiable London market. Oysters never recovered; fishing for oysters gave way to farming them.

Admiralty Courts were held in the Blockhouse, a military stronghold in East Mersea, the outline of which is still visible. The court was held there to emphasise the point that Colchester's control of the river extended to its mouth, whatever Brightlingsea and Mersea oystermen might think.

After 1750, however, the Blockhouse became ruinous. Admiralty Courts transferred to the Moot Hall, but the ceremony at Mersea Stone was continued. So was a boat trip round the river mouth, marking the bounds of the fishery. To make it all worthwhile, a decent meal and several barrels of beer were laid on - at the ratepayers' expense. Naturally, mayor, town clerk, and corporation fancied a dance afterwards.

In 1884, the annual Shutting the River reappeared as the Opening of the Fishery, doubled up with the now ceremonial relic of the Admiralty Court and the sailing of the bounds. It now involved "hauling the first dredges" to check the quality of the oysters, an appropriate gesture now that it was a borough-run business. Next came photography. Increasingly, the mayor, town clerk and town sergeant put on their ceremonial robes for the press. Then, in 1913, an Essex County Standard photographer asked, 'Could the mayor taste one of the first oysters?'. A new tradition was born.

In his 1916 book, Laver rejoiced that the ceremony was now dignified, unlike the 'rough horseplay' of the past. In the 1960s, the tradition was further altered in that the mayor was asked by the press to get into the small and potentially dangerous boat to trawl the first oyster.

Why Gin and Gingerbread?

On board the boat, the assembled people take gin and gingerbread. No-one knows why. Indeed, the only other known reference to this odd combination was made by Dr Johnson in 1774. He observed Dutch sailors (in Scotland) taking gingerbread with gin. Mr Phillips was contacted by a Dutch historian about evidence he had of Dutch and Colchester oystermen co-operating in the 1920s to dredge 70 tons of Colchester and 40 tons of Beverson oysters. Mr Phillips therefore offered this as a promising clue.

(From articles by Andrew Phillips.)

The Oldest Municipal Enterprise an extract taken verbatim from an article by B J Hyde

written around 1907

The fisheries cover a total area of eighteen thousand acres of water, at the bottom of which are countless millions of oysters in all stages of maturity, from the "spat" that is only visible under a magnifying glass, up to "well fished" six-year-olds reposing on the fattening-grounds, fit and ready for the tables of epicures.

The Mayor and Corporation of Colchester, to whom the Colne Fisheries belong, do not actually undertake the working of the oyster-beds. The Fisheries are leased to the Colne Fishery Company, under an Act of Parliament, which reserves to the landlords a rent and percentage of the profits. The absolute management and control is, under this Act, vested in the hands of the Fishery Board, which consists of six members of the Council and six of the Company, who are elected each year.

Some idea of the extent and value of the property may be gathered from the fact that during the last fourteen years no less than thirty-one thousand pounds has been paid to the Corporation, and fifty-eight thousand pounds divided among the members of the Company out of the profits.

The Fisheries are worked by about four hundred oyster-dredgermen, each of whom has to serve a seven years' apprenticeship to a member of the Company before he becomes what is locally known as a "Freeman of the Colne," and, as such, entitled to a share in the profits in addition to the wages received for the work done for the Board on the dredgers or elsewhere.

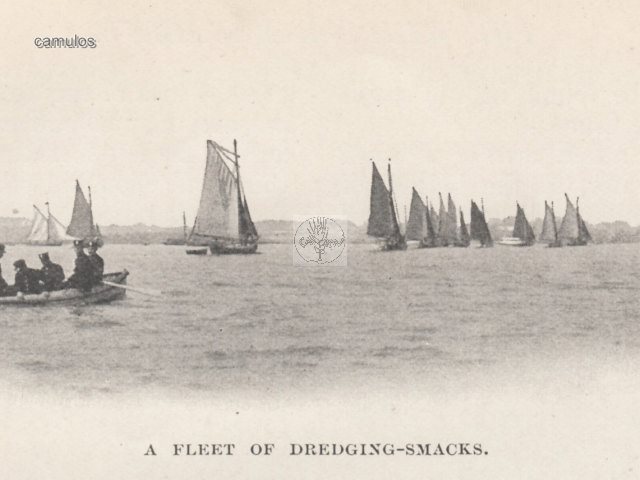

During the fishing season a large fleet of independent dredgers also find remunerative employment dredging in the open sea beyond the Corporation's boundary line, the presence of a continuous supply of oysters in the sea beyond the mouth of the Colne being undoubtedly due to the spat which annually drifts seaward from the millions of oysters in the river, otherwise the outside grounds would long ago have been exhausted by over fishing.

As before mentioned, little is known at present of the real life history of the oyster, though much light has been thrown upon the subject by recent investigations.

The manner in which they feed, their method of propagation, even the sex of an oyster, still remain mere matters of conjecture.

In the summer the oysters sicken and become unfit for food. First comes what is known as the white sickness, during which period the outside edge or frill develops a white, pulpy swelling. This is followed by the black sickness, in which the colour of the pulp turns to black. The oyster then casts its "spat", as the embryo oysters are termed. The spat flows generally in May, leaving the oysters thin and weak.

"Did you ever see an oyster walk upstairs?" queries the writer of an old song. Probably it will be news to him, and also to many others, than an oyster can accomplish this feat with ease, provided always, as the lawyers say, that the stairs were under water, for the embryo oyster often swims, floats, drifts many miles from its original birthplace, before it attached itself to some more substantial object, in order to take upon itself the responsibility of its future existence.

During the spatting season the Colne and the adjacent waters are literally alive with oysters. A single drop taken from the river on the end of a match was found, when examined under a microscope, to contain more than a dozen tiny, yet perfect oysters. Multiply the contents of one drop by the number of drops contained in eighteen thousand acres of water at an average depth of ten feet, and the n umber of baby oysters annually born in the Colne can be easily ascertained. That only a small percentage survive and reach the state of maturity is obvious. Baby oysters attaching themselves, as they do, to any substance with which they come in contact, would soon form themselves into great clusters if not attended to, consequently special beds of "culsh," or bleached oyster-shells, are prepared for them in the river.

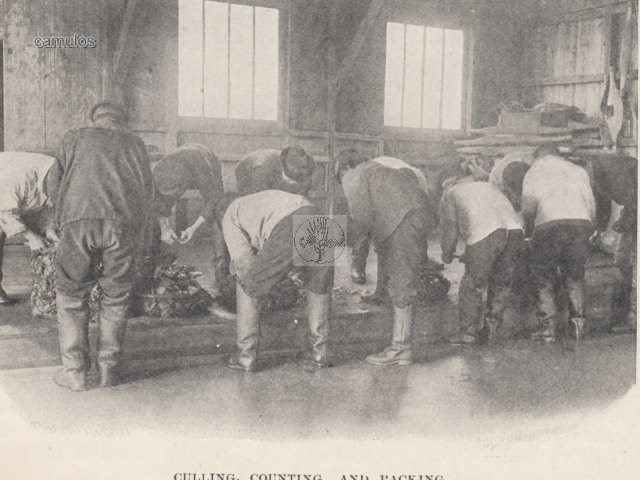

In the early stages, baby oysters are known as "swimming spat"; the exact period for which they float or swim before finally attaching themselves to any object is not definitely known. About the middle of March the work of shifting, stocking, and singling out the brood commences. In order to accomplish this, the dredgermen cull the hauls brought up by the nets. From the older oysters, parasitic growths are carefully removed, so that they may be relaid either in the Colne itself or, if of sufficient age, they are taken to the special fattening-grounds of the Pyefleet.

Often as many as twenty or thirty little will be found attached to one empty shell, and if permitted to mature without being separated, it is obvious that they would be unable to expand and retain the symmetrical shape for which our native oysters are famous, but would, on the other hand, contort and deform one another as they increased in size, so they must be separated and replaced singly in the water.

The singling of the brood is an operation that requires great skill and experience. Each man uses what is known as a "cull tack," takes the brood in his left hand, and carefully separates as many individual oysters as possible from the shell or object to which they have attached themselves. In doing this, innumerable oysters are unavoidably destroyed, as at that stage of their growth the shells are very thin and tenders.

Oysters are not considered in prime condition for the market until they have attained the age of six or seven years. Practically each and every one of the millions of oysters lying upon the beds of the Colne Fisheries will be dredged up, cleaned if necessary, and relaid at least once a year.

It depends very greatly upon the season as to the period which elapses between the time the oysters cast their spat and the time at which they are in a suitable condition for the table. The summer of 1906 was exceptionally favourable, and enabled the oysters to attain a prime condition as early as the beginning of September.

A curious fact about oysters is that one may rest content that a native oyster is actually a native oyster; for though oysters in various stages of maturity are imported from various parts of the world and relaid in other waters, outside the Colne, to fatten, yet, for some unknown reason, foreign oysters relaid on our coasts do not cast any "spat," consequently only the genuine natives breed upon our shores. Many of the foreign relaid oysters, however, are almost as perfect in shape as the natives themselves. If any doubt as to the genuineness of the birthplace of an oyster be entertained, there is a simple means by which this can be proved beyond a doubt. Experts, of course, can tell at a glance, but there is another infallible test which anyone can apply for himself. First open the suspected oyster and remove the fish. If the oyster is a genuine native, the whole of the interior of the shell will be found pearly-white, with perhaps a bluish or purple tinge. If, on the other hand, the oyster has been born elsewhere than in or adjacent to the estuary of the Thames, a dubious, dark, crescent-shaped mark will be observable, somewhat resembling a dark eyebrow, at the point where the oyster was originally attached to the inside of its shell.

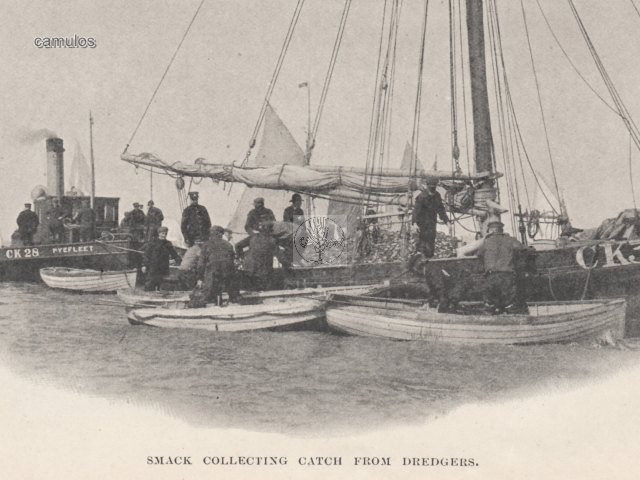

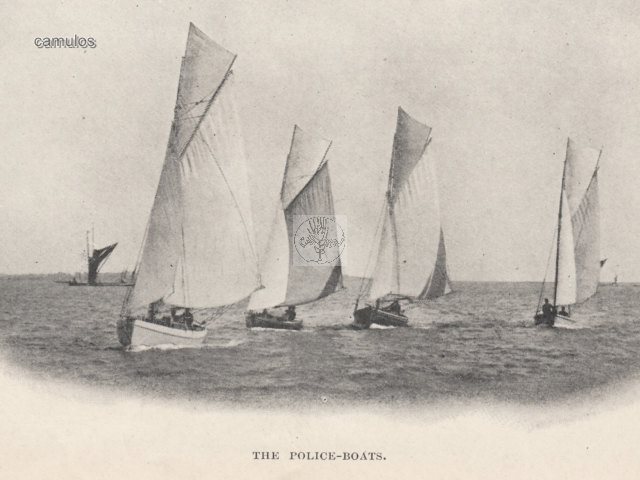

Some pictures from 1907,

taken by W Gill and

showing various aspects of

what was then the

'Oldest Municipal Enterprise'.

These pictures formed a part of the

article by B J Hyde.

(We have searched for B J Hyde

in the 1901 and 1911 census,

but with no success.)

Policing the Oyster Fishery taken from an article by B J Hyde

written around 1907

The price of the Colchester natives has increased enormously during the last fifty years; thus we find that during the great Exhibition of 1862, oysters were disposed of at two guineas per London bushel. This old London bushel contained twenty-two gallons, the price of the oysters working out at about two shillings and sixpence per hundred, or, approximately, the price for which a dozen can be obtained at the present day.

The enormous value of the stock of oysters lying at the bottom of the Colne and Pyefleet naturally necessitates exceptional precautions for the preservation of the property of the Corporation, so that in 1890 a special force of oyster-police was established to protect the Fisheries from the raids of oyster-pirates. This novel police force consisted originally of one chief and three constables. The increase in value and importance, however, has necessitated the increasing of the force to its present number of eight constables, three sergeants, and an inspector, who are to be seen cruising day and night upon the waters of the Colne, either in the cutters or in the steam launch.

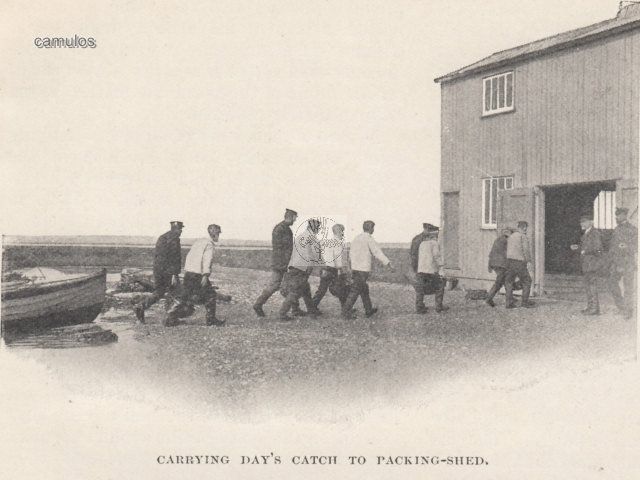

When the Freemen are at work, the Board employ from fifty to one hundred sailing and one steam dredgers. The boats commence operations at appointed places, and at a signal from the flag-boat, "Cease dredging!" each makes the best of its way towards the packing-shed, and an exciting race ensues, the captains of the sailing dredgers manoeuvring to secure the best possible position, each endeavouring to be first to unload her catch. Arriving off the packing-shed, the oysters, which have been previously packed in wicker baskets, are taken ashore in boats. Those not required for immediate packing are thrown into one of the numerous oyster ponds by which the packing-shed is surrounded, there to await the arrival of orders. Inside the shed the packers count and place the oysters in barrels of various sizes. In order that the public who purchase these oysters from the Colne Fishery Board may have a guarantee that the oysters are genuine and in a perfectly healthy condition, a certificate to this effect is enclosed in each barrel, and the barrels are branded with the Borough Arms and fastened with the Board's Seal.

As soon as the fleet have discharged their catch, the oyster-police board and "rummage" the boats, in order to make sure that the men have not concealed any oysters aboard. The regulations of the Board are so strict that no person connected with the Fisheries is permitted to take or eat even a single oyster without payment, and should the police discover even so much as a few empty shells on board one of the boats, the matter would be immediately reported.

As each of the men engaged in the dredging must, of necessity, be a Freeman of the river, and as such, hold an interest in the working of the Fisheries, which is liable to forfeiture, it is seldom indeed that there is any cause for complaint.

The most troublesome parties with whom the oyster-police have to deal are local fishermen, who have an intimate knowledge of the waters and know exactly where the oysters are to be found in the best numbers. When the outside fleet are at work dredging in the waters of the North Sea beyond the limit of the Fisheries, the police-boats must ever be on the spot cruising around to make sure that none of the vessels cast their dredges inside the boundary line.

How profitable oyster-piracy would be to anyone with the requisite knowledge, will be gathered from the fact that a single small dredge cast into the waters of the Colne can collect oysters at the rate of a pound's worth per minute.

The 2015 Opening of the Fishery We offer these images from the Opening of the Fishery ceremony of 4th September 2015 when the great and the good put to sea aboard Hydrogen under the leadership of the worshipful, the Mayor of Colchester, Councillor Theresa Higgins.

We would love to receive images from any year for inclusion here.

Small parties of attendees are taken out to Hydrogen by smaller craft, as dictated by tides and water depth.

Hydrogen out of Maldon come to Pyfleet for the occasion.

The Town Clerk (Mr Adrian Pritchard) reads the proclamation of 1256, accompanied by the Mayor of Colchester (Councillor Theresa Higgins) and the Town Sergeant (Mr Paul Lind).

The trio are conveyed to a fishing smack for the business of dredging the first oysters of the season.

Bringing the haul back to Hydrogen as proof of the catch and its quality.

Below decks for the serious business of the day.

Up on deck for a breath of air and to enjoy the Pyefleet views.

With some more sea shanties from Master Abel Doyle of the Colchester Town Watch, civic bodyguard to the mayor.

Just how old is the Oyster Feast? The following is taken from an article written by Colchester historian, Mr Andrew Phillips and which was published in the Essex County Standard of 7th October 2005.

How old is the Oyster Feast? Why does it exist? Is it unique to Colchester?

Year after year, speakers at the Feast resort to "the mists of antiquity" and "lost in ancient times" to cover their uncertainty. This is not necessary. The origin of the Oyster Feast is absolutely clear, well documented and now to be revealed.

There are clues all over Europe. In Germany they have an Oktober Fest, Nottingham has their Goose Fair, churches from Ireland to Poland hold their harvest thanksgiving. In the season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, Michaelmas daisies offer a last display of flowers to autumn honey bees. Michaelmas (September 29th) marks the turning of the year, the traditional date for renewing business contracts, for settling harvest money, and employing your farm labourers for another year.

With harvest money in their pockets, labourers looked for a Michaelmas fair to buy new breeches, shoes, knives and perhaps a pewter mug. For with harvest gathered in, there was time to hold a feast before the cold winds of winter made you batten down the hatches. Feasts took many forms, but in Colchester the Michaelmas Fair was the St Dennis Fair, held every October 9th on the 'Beryfield' now home to the Colchester Bus Station.

The St Dennis Fair dates from at least 1318 and lasted for a week, craftsmen coming from all over the district with their wares, setting up High Street stalls (under which they slept). It was the big event in Colchester's calendar. The decision to adjust Europe's calendar led to the removal of 11 days in 1752, moving the date of the St Dennis Fair to October 20th.

By this time there were two main Colchester civic feasts. There was the Election Dinner (sometimes the Freeman's Dinner), when these hereditary gentleman elected a new town council, which in those days entered office on Michaelmas Day. On that day was then held the Mayor's Dinner. I'm sure you see the point - keeping the voters happy. Also on the day of the Proclamation of the St Dennis Fair (now October 20th) there was a corporation lunch just for the mayor and the councillors. This much quieter event was marked from at least the 1790s by a gift of October oysters by the Colne dredgermen who had just received their annual licences from the town council. I'm sure you see the point - keeping the bosses happy.

Thus matters remained until 1835 when a major reform of local government forbad all forms of civic feasting. Time to end corruption… that sort of thing. No more Election Dinner, no more Mayor's Dinner. But the little Corporation Lunch (sometimes supper) survived, since they paid for it themselves, except for the oysters which came from the grateful dredgermen.

In 1845 the new mayor was Henry Wolton, a great traditionalist. For example, he re-introduced the punishment of the stocks for persistent drunkards - a practice by then unknown elsewhere. He also dramatically renamed the Corporation Lunch, inviting 200 guests to dine at his expense in the newly-built town hall (the one before the present one). Wolton had invented the modern Oyster Feast, by cleverly re-inventing the banned Mayor's Dinner. For this he was re-elected mayor FIVE TIMES.

Not all subsequent mayors were as generous as Wolton and not till 1878 did another wealthy mayor, Thomas Moy the coal merchant, make the Wolton Oyster Feast the normal thing. Before long, cabinet ministers and London dignitaries were coming down to Colchester as our guests, to be followed in the 20th century by showbiz and media personalities, to give the event popular appeal. By now the St Dennis Fair was no more, last seen as a horse fair near the bottom of Ipswich Road. It was last 'proclaimed' by the mayor and town council in 1938.

So there you have it? 1318 St Dennis Fair, 1790s Corporation (Oyster) Lunch, 1845 modern Oyster Feast, all (after 1752) occurring in late October. This is, I believe, the first complete account published of the descent of the modern Oyster Feast. And how old is it? Don't worry, the question is sure to be asked again. But all you have to do is cut out this little article, and put it in a safe place.

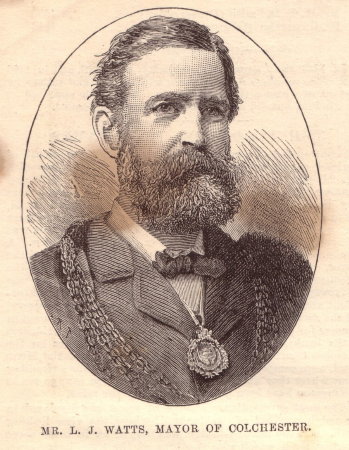

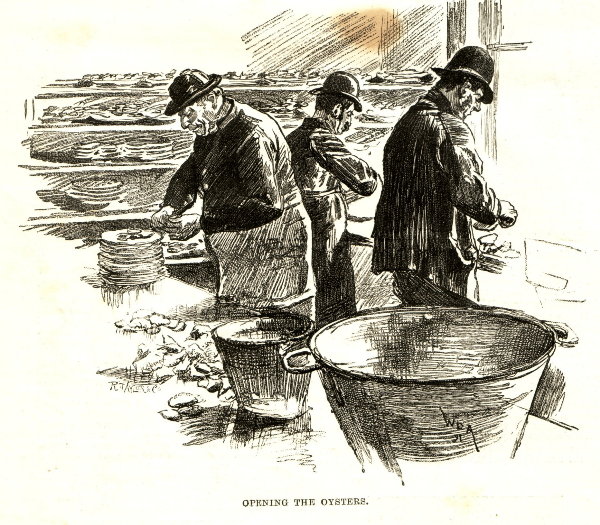

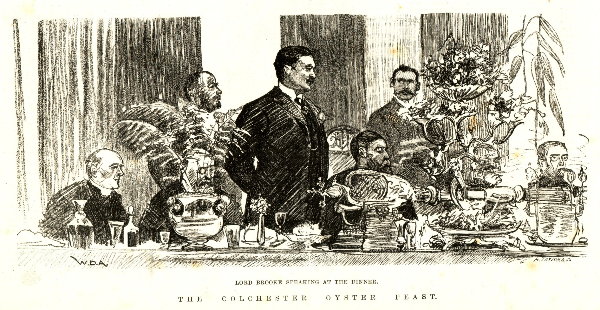

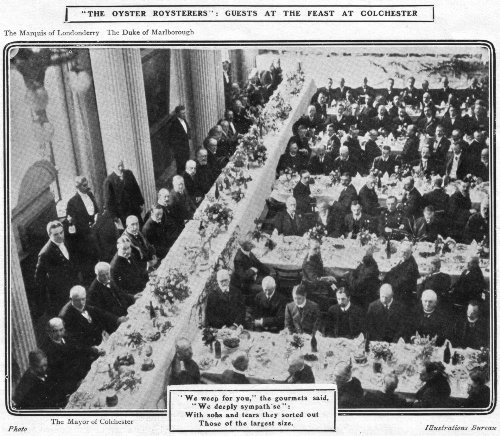

These are images from the

Illustrated London News

dated 31st October 1891

concerning the

1891

Colchester Oyster Feast

Mr L J Watts

Mayor of Colchester

The Town Serjeant Conducting

the Guests to Dinner

Opening the Oysters

Lord Brook Speaking at the Dinner

And so, Ladies and Gentlemen,

here follows

various other depictions

of the

COLCHESTER

OYSTER FEAST

for your delight

and delectation.

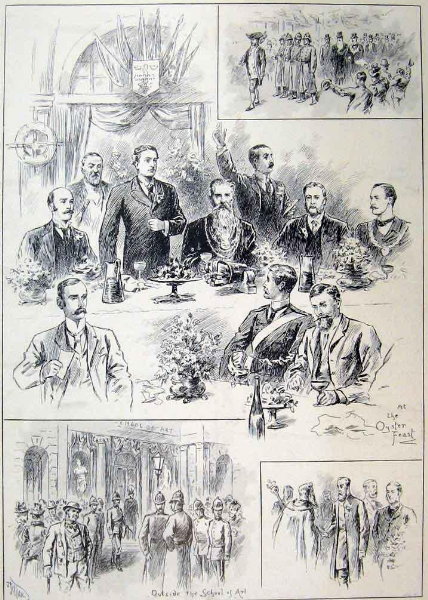

From the Illustrated and Dramatic Sporting News in1896

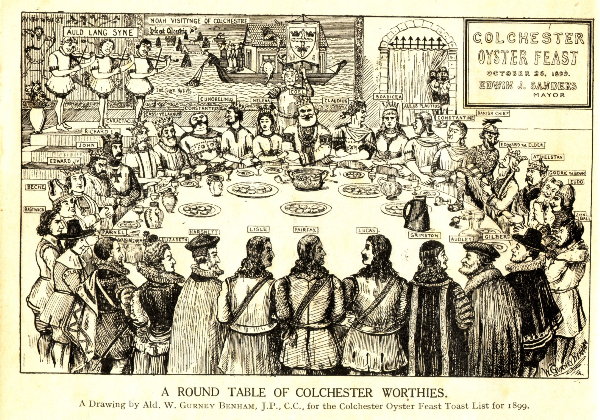

From 1899

From 'The Bystander' of October 30th 1907

The Oyster Feast of 1908 was robbed of its guests and other leading personalities because the date of the feast, October 25th, was the one which the memorial service to Princess Marina was to be held. Guests who had to cancel their attendance at the feast were Prince Georg and Princess Anne of Denmark, Earl Mountbatten and the Belgian Ambassador.

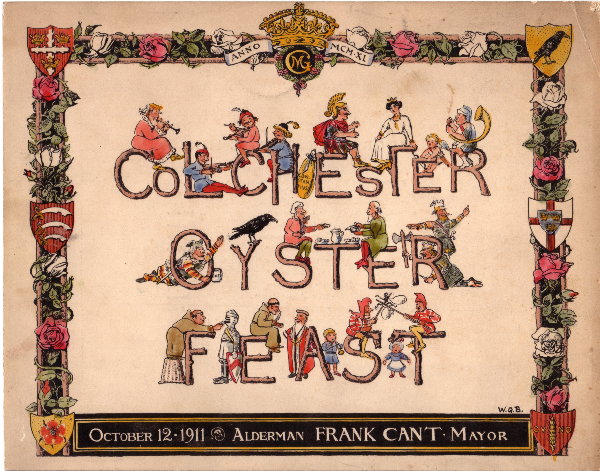

From 1911,

when

Alderman Frank Cant

was Mayor of Colchester

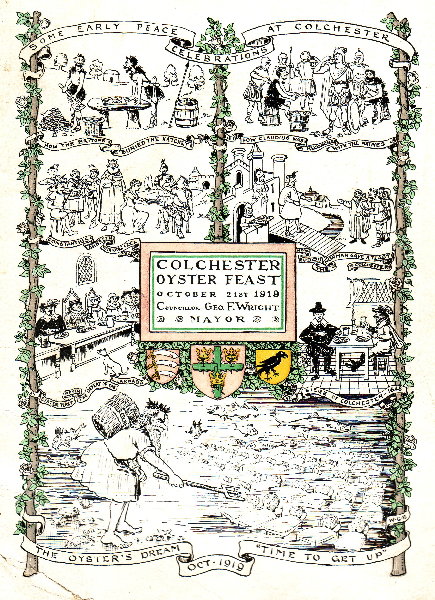

From 1919

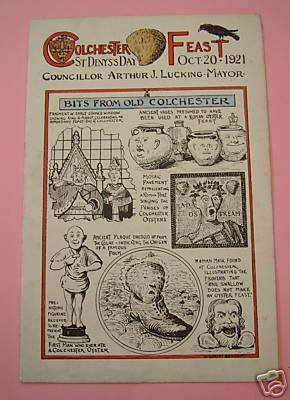

Colchester OYSTER FEAST PROGRAMME from October 20th 1921.

Card Programme with Toast List. The Mayor at the time was Arthur J Lucking.

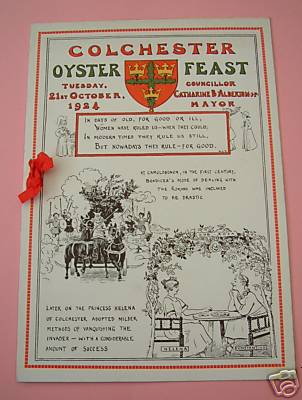

Colchester OYSTER FEAST PROGRAMME from October 21st October 1924.

Card Programme with Toast List. The Mayor at the time was Catherine B Alderton.

The following pictures are of programme of the Colchester Oyster Feast of Thursday 20th October 1927. This was hosted by Councillor C C Smallwood, Mayor of Colchester. The programme was designed by W Gurney Benham. The toast list includes such personages as:

J L Garvin, Esq

Editor of the Observer

The Rt Hon Sir Austen Chamberlain, KG MP

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

The Rt Hon J Ramsay MacDonald, MP

R Seebohm Rowntree, Esq, MP

The Rt Hon J H Whitley, MP

Speaker of the House of Commons

Hillaire Belloc, Esq

Sir Thomas Horder, KCVO, MD, BSc

Miss S M Fry, JP, MA

Somerville College, Oxford

Frank Hodges, Esq, JP

Sir Evelyn Murray, KCB

Secretary, General Post Office

J W Bowen, Esq

Union of Post Office Workers

The Hon Sir Malcolm M Macnaghten, KBE, KC, MP

Recorder of Colchester

The Rt Hon Lord Olivier, PC, KCMG

The Rt Hon The Lord Provost of Glasgow

David Mason, Esq, OBE

1927

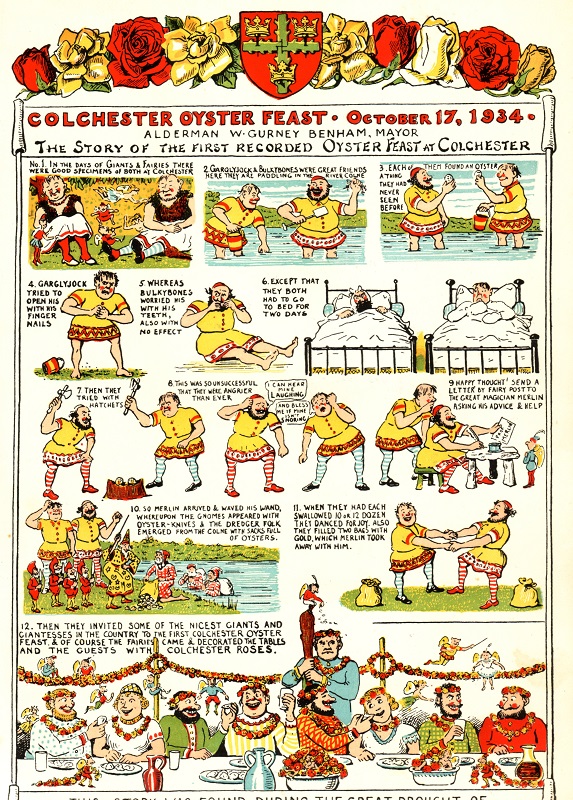

from 1934

when Alderman W. Gurney Benham was

Mayor of Colchester

No. 1 - In the days of Giants and Fairies there were good specimens of both at Colchester.

No. 2 - Garglyjock and Bulkybones were great friends. Here they are paddling in the River Colne.

No. 3 - Each of them found an oyster, a thing they had never seen before.

No. 4 - Garglyjock tried to open his with his finger nails.

No. 5 - Whereas Bulkybones worried his with his teeth, also with no effect.

No. 6 - Except that they both had to go to bed for two days.

No. 7 - Then they tried with hatchets.

No. 8 - This was so unsuccessful that they were angrier than ever. I can hear mine laughing and bless me if mine isn't snoring.

No. 9 - Happy thought. Send a letter by fairy post to the great magician Merlin asking his advice and help.

No. 10 - So Merlin arrived and waved his wand, whereupon the gnomes appeared with oyster knives and the dredger folk emerged from the Colne with sacks full of oysters.

No. 11 - When they had each swallowed 10 or 12 dozen they danced for joy. Also they filled two bags with gold, which Merlin took away with him.

No. 12 - Then they invited some of the nicest giants and giantesses in the country to the first Colchester Oyster Feast and of course the fairies came and decorated the tables and the guests with Colchester roses.

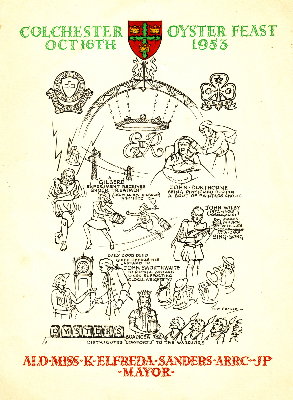

1953

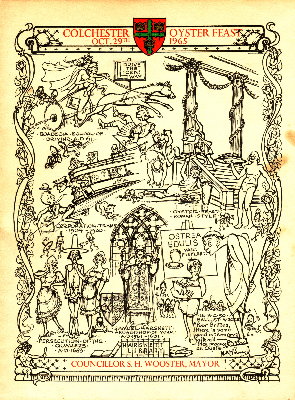

1965

This page hosted by:

Page created

7th October 2005

revised 3rd September 2016

reposted 11th August 2020