[HOME]

A

TOUR

OF

COLCHESTER

CASTLE

Aussi une petite histoire rapide en francais ici.

Not as good as the real thing - but it will have to do!

The castle interior was extensively re-modelled during 2013 and 2014. This web page will give you details from both 'before' and 'after' the re-fit. We will try to show and explain the principal points of interest for the castle, although the structure and its modern day contents are so extensive, I will only be able to scratch the surface of what this magnificent building has to offer.

This unofficial tour will start by talking about the Norman building.

It will then move on to the Pre-Roman period exhibits. Click here to move to this section.

It will then move on to the Roman period exhibits. Click here to move to this section.

It will then move on to the Post-Roman period exhibits. Click here to move to this section.

It will then move on to the Norman period exhibits. Click here to move to this section.

It will then move on to the Medieval period exhibits. Click here to move to this section.

It will then move on to the Civil War period exhibits. Click here to move to this section.

Colchester Castle was built by the Normans (from Normandy in France) from around 1076, as part of their defence system, following their invasion of England in 1066. It is an impressive structure, indeed the largest Norman keep ever built and the first to be built by William the Conqueror in England. His steward (or dapifer) Eudo de Rie, carried out the initial building work.

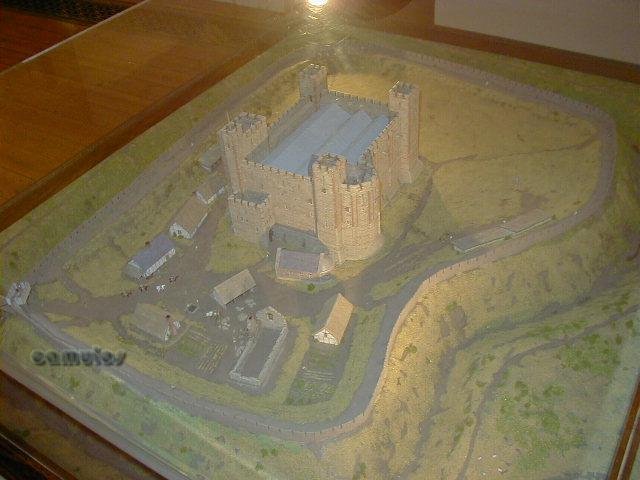

1

This model in the picture above shows an interpretation of how the finished keep and bailey might have looked around the year 1100. The following picture is taken from a similar south easterly direction, some 900 years later. The model shows the extensive outer bailey walls, within which the massive keep was built. Its great size is due to the fact that the keep was built around the podium of the Roman Temple of Claudius, destroyed by the Iceni Queen Boadicea in AD 60 or 61. This must have been a place of great significance to the English, whom the Normans had conquered, and with the Normans wishing to attach their authority over the powerful magic of the location.

2

(taken September 2016)

The castle is built almost entirely from reclaimed Roman materials, roof tiles being in abundance and heavily used in the walls. The large windows in the above view are not original but put in by Charles Gray in the 18th century, to give more light, replacing the smaller Norman slit windows that would once have been there. This building was constructed as a barracks for Norman soldiers; a place of safety against attack, but also one where perhaps 2000 soldiers could get out quickly in the event of trouble. The original slit windows can be seen elsewhere on the building faces - but more of this later.

3a

3b

(taken September 2016)

These much decayed foundations are believed to be of an earlier apsidal church or chapel structure, interconnected with a later Norman section, with its tell tale tapered slit window evidence. What we are looking at is the result of a 1930 archaeological dig that uncovered these foundations and gave us so much more knowledge about our castle's evolution.

3c

3d

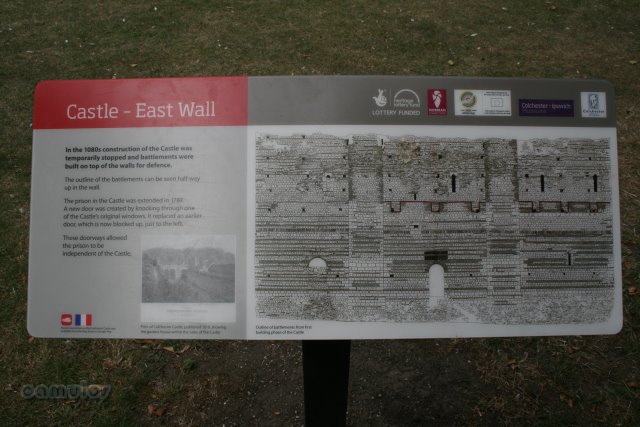

3e

3f

(taken September 2016)

The three pictures above are of information boards that have recently (2016) been installed around our castle. So, whilst we are here, let's indulge ourselves with a few more images of some of the reasons why Colchester's award winning castle park is the 'jewel in the crown' of Colchester.

3g

3h

3i

(taken September 2016)

3j

3k

3l

(taken September 2016)

4a

The present day foot bridge leading into the castle keep spans these older foundations and takes the visitor through a typically magnificent Norman archway. Opinion is divided as to when this door was added and what form it took, whether it would have had a drawbridge, portcullis, etc. Note the cupola and tree at the top, both late additions to the original. More of which later!

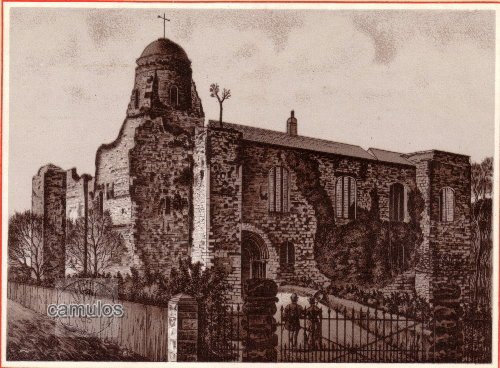

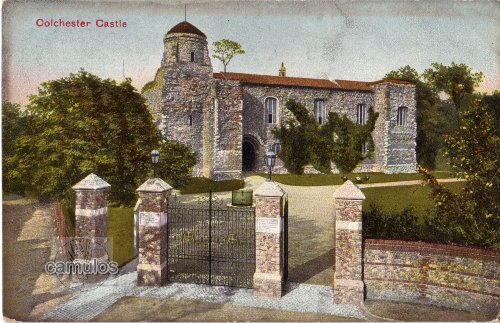

Here follows a couple of old postcards, more of which may be found here.

4b

4c

Upon their arrival, the Normans soon discovered that Essex was devoid of any natural building stone. The Romans had found the same thing some 1000 years earlier and had used a material called septaria, some of which could be mined nearby (or which had to be brought from the coast), and the naturally occurring red earth, from which they made their tiles.

England was soon under threat from another invader, King Cnut of Denmark. As I will discuss later, building works were modified to cater for this threat, with a later addition in height being made. The invasion never came and it is thought that the castle was finally completed around 1125. The castle did come under attack in 1216 when it was beseiged for three months and eventually captured by King John, after he broke his agreement with the rebellious nobles (Magna Carta). By 1350, its military importance had diminished and the building became mainly used as a prison. By 1600 it was no longer defensible and by 1637, the roof to the great hall had fallen in. In 1629, the castle was sold by the crown. In 1683, it came into the possession of John Wheeley, a local ironmonger., who set about the destruction of the building with a view to profiting from the sale of the building materials to local builders. In this he failed, and went bankrupt in the process. However he did discover the presence of the Roman temple foundations, which he partially excavated in the mistaken quest for hidden treasure.

In 1726, after having had several owners, Charles Gray (MP for Colchester at that time) acquired the castle and its grounds as a marriage gift. He set about restoration and alterations.

Lingering at the walls (we will go inside soon), it is quite clear that the castle was built in more than one stage. An extra storey was added at some point, evidenced by filled-in battlements in various places (see picture 4 above) and different style (ie cheaper) of corner stone work (quoins). The roof is of Italian style and is not original. Charles Gray had believed his castle to be Roman and saw fit to put a Roman style roof upon it.

Looking up again to the walls, there can be seen a sycamore tree growing on the ramparts, said to have been planted by the gaoler's daughter, some 200 hundred years ago. The castle served as the town's gaol for many years. Also, the west wall is basically as it was when the castle was first built, with its tiny slit windows which gave light internally and kept the worst draughts away. Also in this wall are various outfalls from the garderobes, the toilets! The round cupola on the top was built for Charles Gray and is in the position where one of the castle towers would once have stood. It is likely that Wheeley demolished these towers prior to Charles Gray's rescue. 'Put' holes are to be seen all over the walls, both inside and outside, where the original wooden scaffold poles would have been 'put' during the castle's construction. Most of these have since been bevelled with mortar to deter pigeons.

5

Part of the west wall above. Note the vertically stacked red tiles that form one of the courses of the building's fabric. These are Roman hypocaust pillars that once held up the heated floors of high status Roman houses. Of no further use, they have simply been re-used by the Normans. In fact, the Normans very efficiently destroyed Roman Colchester in their quest for building materials - with the exception of the town's wall, which was far too strategically important to touch. Yes, the Norman building style was one big botch! Totally haphazard and unattractive and purely functional.

6

Also from the west. The two small apertures are from the twin toilets that are to be seen inside the castle. Perhaps 'his' and 'hers'.

7

(taken September 2016)

....and a view at the rear (from the north side looking down towards the River Colne) showing the Norman period rear (the main entrance for day to day access) entrance to the keep, that would once have had a secure stairway up to it. The large door to the front of the castle would probably only have been opened in an emergency or for troop movements or for horses and wagons.

In 1860, the crypt was opened to the public as a museum. In 1920, the castle was presented to the borough by the Viscount Cowdray, as part of the planned War Memorial that was built a short while later. In 1934/5 the castle keep was roofed over, leading the way for the development of the museum, to the form in which we see it today.

Let us now go inside and have a look around!

WARNING - What follows is from a time before the extensive work was carried out to transform the display space. At the end of the page we will show some of how the castle interior looks today.

8

The great arch leading into the castle keep is shown above, with some of the members of the Colchester Town Watch on duty.

9

Once through the great arch, to the left will be seen the great stairway, spiralled to the right as you go up. You would have to play the role of sword wielding attacker and defender to realise the wisdom of the direction of the spiral. You might think that the builders had allowed an advantage to a right handed attacker, allowing him to swing his sword so advantageously against a defender coming down. Think again. Yes, the defender was standing on a narrow part of the step but, he was tucked in, around a corner, able to deliver a powerful downward slash against his opponent. Clever people those Normans!

10

To the right will be found the all essential well, where fresh water could be had during a period of siege or in time of peace. As has already been mentioned, Colchester was built on a hill, with no natural flowing water or springs. It was a place of defence and to observe the surrounding land. A well was essential.

The moral here is that a photographer should keep his size 10 boots out of the picture. There is probably a mixture of Roman and Norman masonry in the well shaft and, nowadays, many coins at the bottom, put there by the superstitious among us over many years. It is a valuable source of funds for the council!

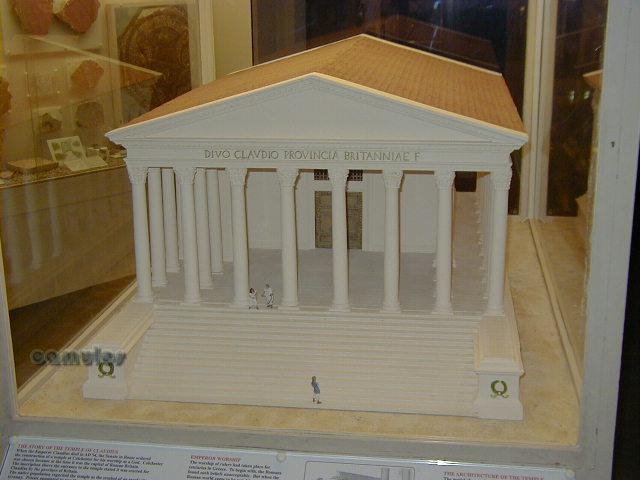

11

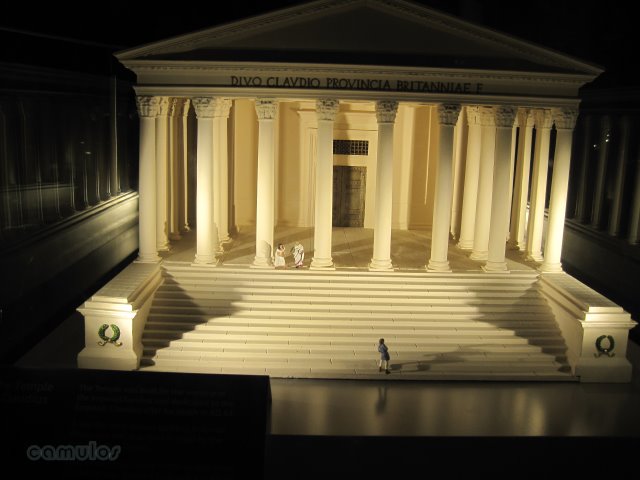

As I have previously mentioned, a previous owner of the castle was a man named Wheeley who had bought the building for the sole purpose of demolishing it and selling off the materials for building works. Thankfully, the task defeated him and he went bankrupt as a result. During his endeavours, he discovered the Roman podium of the Claudian temple, around which the castle was built. It could be argued that this would never have been discovered, had he not carried out his demolition work, as modern day conservation might have prevented such invasive exploration. From contemporary examples elsewhere, it is believed that the temple would have looked like the model shown above.

Perhaps Wheeley did us a favour after all.

It is conjectured that, the height of the castle as you see it today is about what it was when it was first built, although the corner battlements have mostly disappeared. Incidentally, our castle predates and is built double plan scale to the famous Tower of London. That building has fared better with the passing of time and must surely be a good indicator of how our castle must once have looked.

12

The above picture shows one of the magnificent fireplaces that would have been built in the second phase of construction of the keep. Note the herringbone pattern that the Normans favoured when re-using the Roman tiles.

13

A little further along, the Norman toilets. A hole in the floor, presumably originally furnished with a comfortable seat and door. The outlet was via a chute on the outer wall, as seen in picture 6.

Now we take a look down in the dungeons.

'Abandon hope all ye who enter here!'

14

A gruesome set of display boards give information about crime and punishment in bygone days.

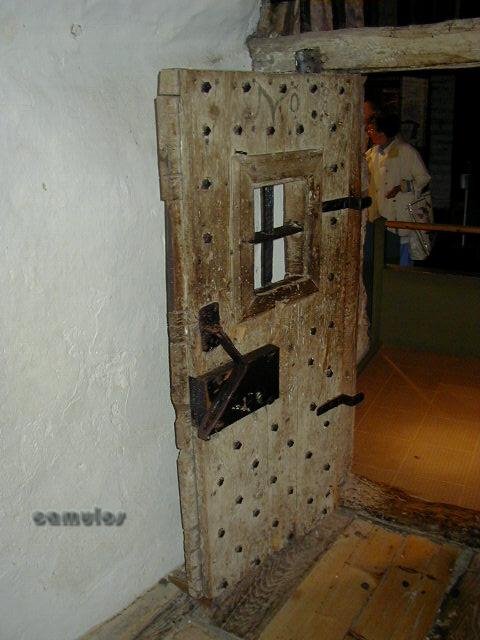

15

The door of the dungeons (the jail or gaol).

The French called castles 'donjons'. Being at war with the French for many years, the English took the word to mean a bad place and named the cells as the dungeons, a misuse of which name has been with us ever since. The French word for dungeons is 'oubliettes' which means 'forgotten'.

16

This picture shows the two main cells, perhaps to separate male from female inmates. It must have been a very bleak place to have ended up.

This concludes our interior tour of the castle's structure, although further details will be added at a later date for other areas not normally open to the public, such as the roof and the Roman foundations. These are covered by a separate guided tour. This tour will now continue with some of the exhibits which can (or once could) be viewed within the castle.

up to 43 AD

17

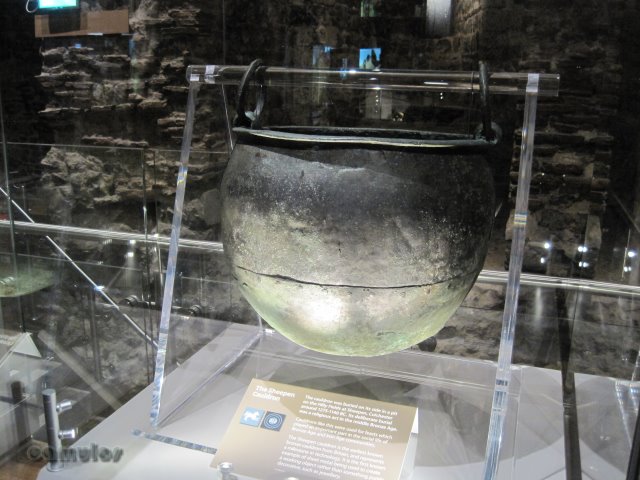

The Sheepen Cauldron above was discovered by archaeologists in the Sheepen Road area, associated with a time before the Roman invasion and where King Cunobelin minted his own coinage.

18

Bronze artefacts, believed to be a hoard destined for melting down and re-used, perhaps for coin minting. Iron was to become the new metal for weapons, being much stronger and durable.

19

Archaeoloigical finds from the Iron Age period associated with all aspects of life, with an illustration of how a homestead may have looked during that period around 100BC.

20

King Cunobelin, son of Tasciovanus, lived from c AD 5 to c AD 40. He was the most successful of the kings (or chiefs) of Iron Age Britain. At the start of his reign he conquered the Trinovantes and his power spread throughout south east Britain. The illustration depicts the secret of their success, the use of open chariots that could be driven very skilfully with added protection of the extensive Iron Age dyke system, evidence of which can still be seen in Colchester today.

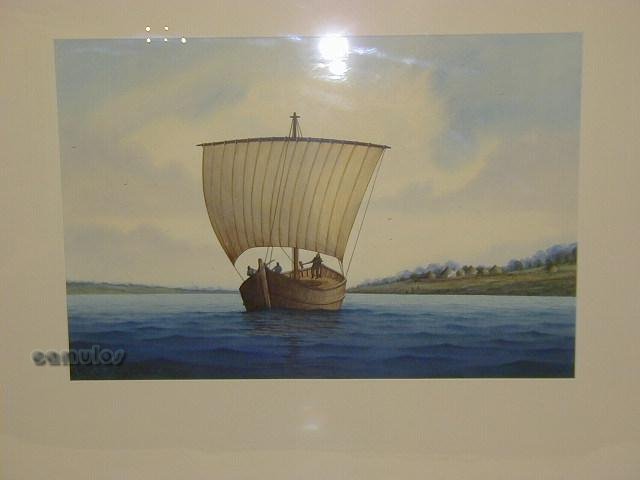

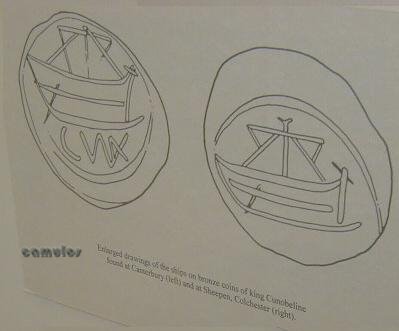

21

This is a painting that was specially commissioned to show what it is believed an Iron Age ship would have looked like, sailing up the River Colne, some 2000 years ago. It is based a coin of Cunobelin (illustrated below), whose death it was that precipitated the arrival of the Roman invasion forces in AD 43. The artist was Frank Gardner.

22

AD 43 to 410

23

On the ground floor we are introduced to the Roman period with a reconstructed warrior chariot as actually used in the filming of the ITV film 'Boudica' around 2002. Alex Kingston starred as the British queen who rebelled against the Romans and their control. The chariot is based on a known Iron Age design and would have been used for moving people around the battlefield. We will now go up to the first floor of the castle.

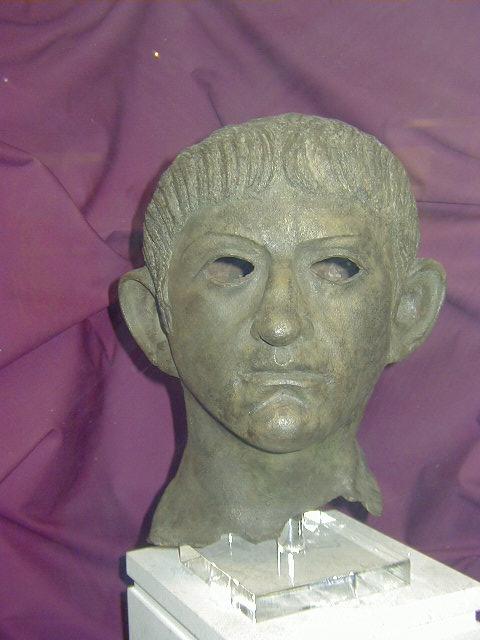

I start with this bronze bust, believed to be that of the Emperor Claudius, found in a nearby river, suggesting that it was a prize taken by one of Queen Boadicea's followers after her destructive visit to the town.

24

Perhaps it was part of a much larger statue that might once have taken a prominent position in some lavish Roman building of the time.

It should be remembered that, whilst this section covers the Roman period, there was a thriving community of indigenous British people living alongside and amongst the Roman community. The following pictures are part of a superb display covering the British community during the early Roman period, say from AD 43 AD to 100.

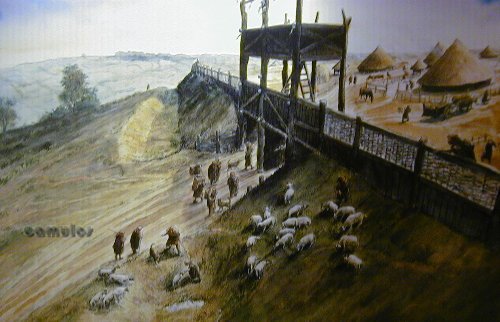

25

This picture shows what a typical defensive walled enclosure would have looked like with a wooden palisade wall, defensive ditch and bank and with the typical Iron Age roundhouses, evidence of which has been found all over the area and throughout this part of Britain.

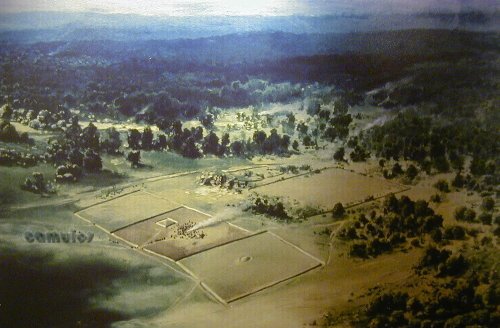

26

This picture shows an aerial view of what we now call the Gosbeck's Archaeological Site, showing the extensive defensive ditch and dyke system, enclosures with dwellings and burial mounds, etc.

27

In the 1990s archaeologists discovered a warrior's grave, and nearby, what has been called the Doctor's Grave. Inside the incredibly well preserved burial chamber was found a set of medical instruments, together with many other objects which also included a gaming board and pieces laid out as if the doctor had been in the middle of a game.

28

These items were taken from the Doctor's Grave which dates from around the year AD 50.

29

This shows a recreation of a burial pyre, used to cremate a dead body. This was from a day when wood was in good supply and could be used for burning the dead.

This set of exhibits have since been removed, but we keep them here because it was such an excellent portrayal of our Romano-British heritage.

Moving on to a more Roman theme, we are overwhelmed by the extent of the exhibits that are on display in the castle.

30

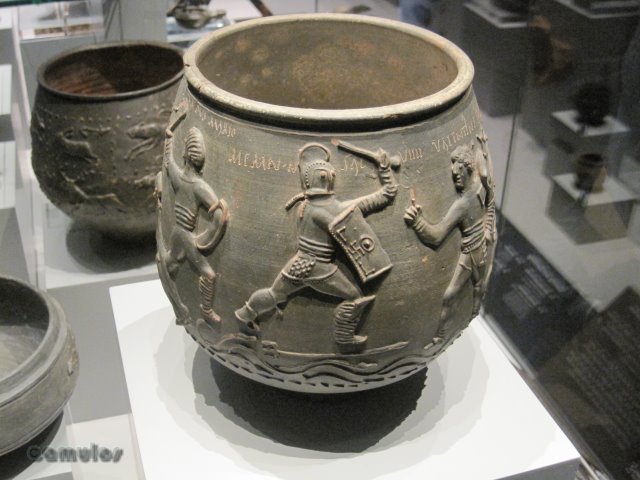

The exquisite Colchester Vase. Very well preserved, this face shows two gladiators in action, a pastime that probably occurred in the colonia during important occasions. It dates from AD 175 and was probably made in Colchester. Four gladiators can be seen on the vase. Above them are inscribed the names Secundus, Mario, Memnon and Valentinus. It is one of the finest examples of ceramic art known from Roman Britain.

31

The Colchester Sphinx. Found in a burial area to the west of the town.

32

Examples of antifix mouldings. These were fitted to tiled roofs and often depicted gods or godesses to ward off evil spirits.

33

A closer view of the antifixes.

34

35

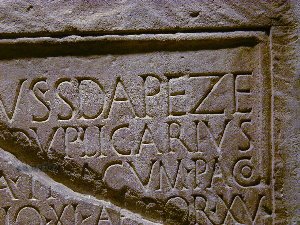

This is the famous stele of auxillary cavalryman Longinus Sdapeze. Also shown is a part of the inscription.

Here follows a tombstone (or stele) to legionary centurion Marcus Favonius Facilis, dating from around AD 100. The inscription at its base reads:

MARCUS FAVONIUS FACILIS SON OF MARCUS OF THE POLLIAN TRIBE CENTURION OF THE TWENTIETH LEGION VERECUNDUD AND NOVICIUS HIS FREEDMEN SET UP THIS HERE HE LIES

36

This stele, together with that of Longinus Sdapeze, are some of the finest examples that have been found in Britain.

37

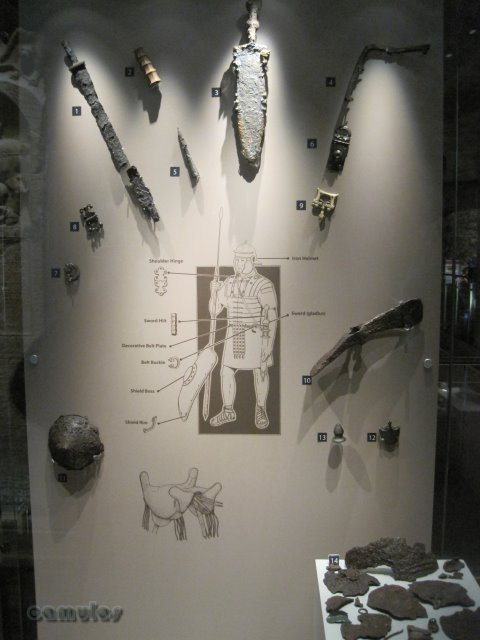

Mark Griffin is seen here working with visitors to the castle, dressed in Roman gladiatorial tunic and demonstrating the protective equipment used.

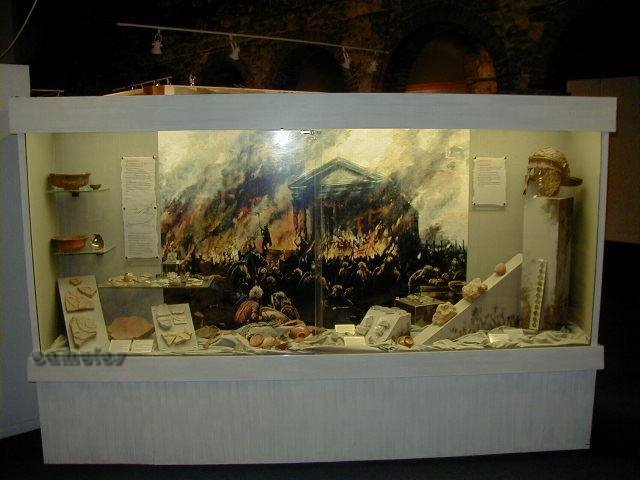

38

A display cabinet devoted to the Boudiccan rebellion, showing the destruction of the Temple of Claudius in or around AD 61.

39

One of the many display cabinets showing finds from the year 2000 Post Office dig.

40

Examples of oil lamps from the Roman period

41

Jewellery finds from the Roman period

42

Human remains from Colchester's Roman period, with clear evidence of bone disease.

43

Face urns for cremated remains are common finds. This one was perfectly preserved due to its tile lined cavity set in the ground.

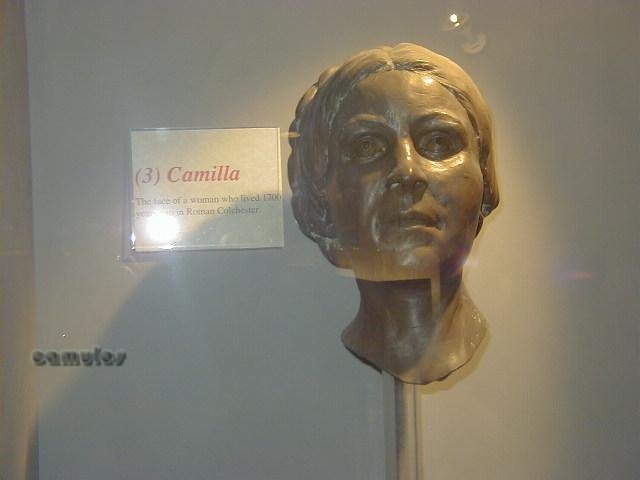

Camilla was an attempt at recreating the face of a woman using her skeletal remains. She was discovered in the huge graveyard of the Butt Road area alongside what is believed to have been her husband. Her skull was used to model how it is thought she would have looked in the 4th century. Camilla forms the basis of 'The Camilla Project' where archaeologists are trying to determine a link between her and modern day descendants. Go here for more details of this.

45

A small Roman period mosaic and wine amphora, all discovered in Colchester. They are located in one of the Norman period archways of the castle.

410 to 1066

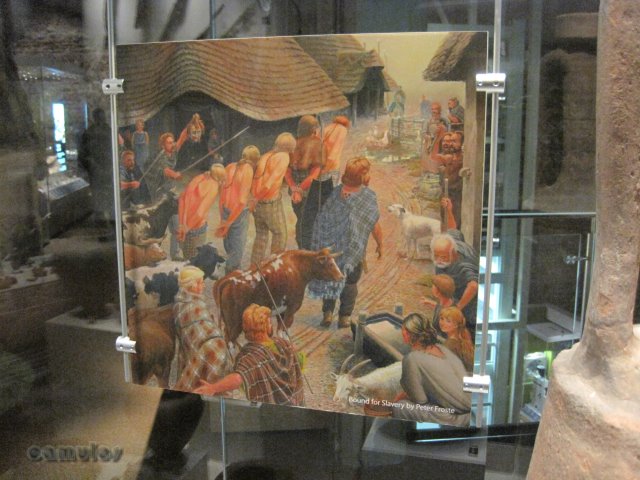

As might be expected, the exhibits for this period are considerably less than that for the preceding Roman occupation period. This case displays Saxon artifacts including weapons, pottery, jewellery, weaving weights, etc.

46

The Saxons were not town dwellers and, after the Romans departed, the town fell into decay. Finds from within the walls are therefore very few.

47

A model of a Norman soldier, located in one of the niches of the crypt of the castle.

48

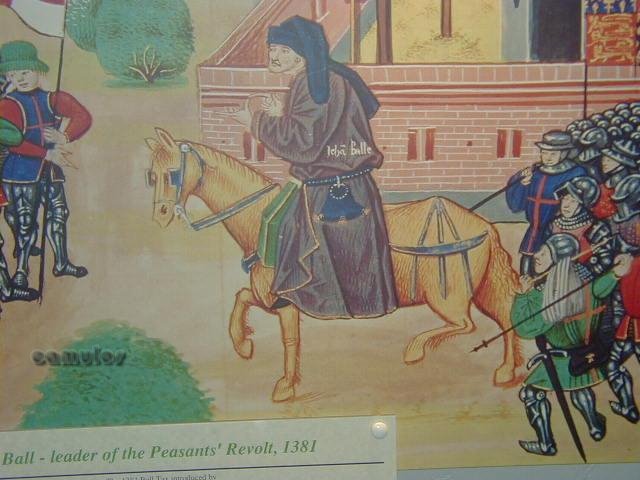

The Black Death of 1348/9 killed approximately one third of the population of Europe. This resulted in a labour shortage. Peasants began to demand better conditions and a share in the wealth they created.

In Colchester, the priest,John Ball, preached against the greedy, idle lives of nobles, merchants and church leaders, which the common people worked to support. The 1381 Poll Tax introduced by Richard II finally pushed the common people to breaking point.

Imprisoned for his teaching in Kent, Ball was released by the rebels of the Peasants' Revolt he had worked to bring about.

Despite widespread support, the revolt failed, following the death of its other great leader, fellow Colchester man, Wat Tyler. Ball was hung drawn and quartered for his part in the revolt and is remembered today as one of England's first revolutionary leaders.

49

50

This timber framed building structure was rescued in the 1930s from a location in Culver Street.

51

Medieval pottery artifacts.

52

More medieval pottery.

53

A display above and below discussing Colchester cloth trade, with a picture of St Peter's Church drawn with a lot of artist licence to please the vicar who commissioned the work. Colchester was once one of the wealthiest cloth towns in the country, perhaps in the top six and much to do with Flemish weavers who came here in the 16th century to escape religious persecution.

54

55

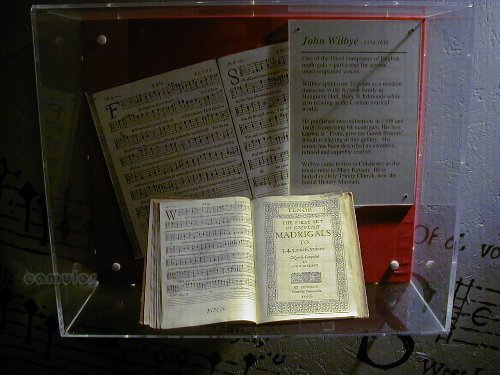

A display of the work of John Wilbye, a writer of madrigals, who once lived in Trinity Street. A plaque to his memory is on his house, near to the library.

An example from the castle's Civil War period exhibition, when Cromwell's forces besieged the town in 1648.

56

57

58

59

Charles Gray once owned the castle, having been given it as a wedding present. We have him to thank for its rescue and preservation and his heirs for the castle being given to the people of Colchester.

Here follows some images of how the castle interior looked after 2015,

following a multi-million pound re-fit.

Much of the previous layout has been lost.

What do you think?

60a

60b

60c

Recycled Roman tiles used for the Norman building.

60d

60e

60f

60g

60h

Valentinu.

60i

Memnon.

60j

Willies. Lots of em.

60k

60l

60m

60n

60o

60p

60q

60r

60s

60t

60u

60v

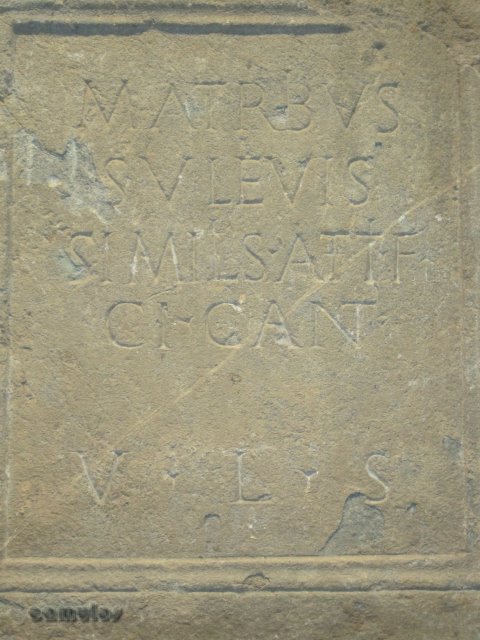

The Temple of Claudius. Over which the castle was built.

60w

The Doctor's Grave at Stanway.

60x

60y

Longinius Sdapeze and Marcus Favonius Facilis.

The Roman soldier in teh foreground was trying on some kit.

60z

61a

61b

61c

61d

An Iron Age Round House.

61e

Bronze Age cauldron.

61f

61g

61h

61i

Here you can race a chariot around the circus.

61j

61k

THE END

Please remember that this is an unofficial, virtual tour of the castle. We hope that you have found it informative.

At one time, the castle could be visited for free. That is no longer the case.

return to the

Home Page

reconfigured

221021

Rapide Historique du Chateau de Colchester. En 1066, les Anglais furent battus par l'armée du Duc Guillaume le Conquérant (Duc Guillaume de Normandie). Après sa victoire à la bataille d'Hastings, le renforça alors ses positions sur les Anglais vaincus en faisant construire des châteaux dans tout le pays. La ville de Colchester fut choisie par le Duc Guillaume pour son port et la position militaire stratégique qu'elle occupait, assurant le contrôle de l'accès sud-est de l'Angleterre. En 1076, la construction du Château de Colchester commença. Ce fut le premier château royal en pierre construit par Guillaume en Angleterre.

La forteresse, qui reste l'une des plus importantes jamais bâtis par les Normands, fut construite autour des ruines du gigantesque du temple de Claudius. Pour la majeure partie, les Normands réutilisèrent les matériaux de construction déjà en place sur le site des ruines romaines et importèrent des pierres en complément.

En 1126, le Château fut finalement terminé. Il disposait alors de trois ou quatre étages. Cependant, en 1216, le Roi John le prit d'assaut et l'assiégea pendant trois mois. Au terme de ce siège, et malgré sa position et la robustesse de son édifice, le château dut se rendre. A partir de 1350, son importance militaire déclina et on utilisa le bâtiment comme prison. Vers 1600, son état ne lui permettait plus d'assurer son rôle défensif et protecteur. Vers 1637, le toit de l'entrée s'effondra.

En 1629, le château fut vendu et c'est un quincaillier de la région qui l'acheta. Il en entreprit la démolition partielle pour vendre les pierres aux maçons des environs.

Ce n'est qu'en 1726 que Charles Gray, membre du parlement de Colchester, obtint ce qui en restait. Il restaura et modifia l'édifice.

En 1860, la crypte fut ouverte au public et en 1920, le château fut offert à la municipalité de Colchester.

En 1934, le donjon fut recouvert d'un toit et aménagé pour devenir le musée actuel. De nos jours, le musée abrite une des plus belles collections d'art roman de Grande-Bretagne et propose de découvrir la vie des anciens habitants de Colchester de façon interactive et originale.